Lest We Forget: Three Stories to Honour Millions

Every year on November 11th, we remember the fallen soldiers from our community and our country who made exceptional sacrifices to pay for the freedom and prosperity that we have today. It is ironic that these blessings sometimes make it difficult to comprehend the scale of the tragedy, the tangible horrors of war, and the personal impact of the losses.

This profound suffering was shared by almost every Canadian family, including the three families - the Browns, Chellews and Powers - who called The Brown Homestead their home from 1785 to 1979. Today, we share the stories of these three fallen servicemen. Once again, we ask the impossible of them by asking them to stand for the countless who never came home and who risked everything to serve.

The young men were Douglas Magrath, the third great-grandson of John and Magdalena Brown; Frederick Read, the grandson of Joseph and Eliza Chellew; and William Powers, the grandson of Lafontaine and Mary Ann Powers.

Douglas Magrath was a fifteen year old student in Windsor, Ontario, when Canada declared war on Germany. Keen, alert, and wiry, the third of 8 siblings, he was still playing hockey and basketball at Walkerville Collegiate Institute when conflict swept the world. As Douglas was finishing secondary school, working as an office boy, and then a purchasing clerk, France surrendered to the military might of Germany, the U.S.S.R. was invaded, and the United Kingdom survived the Blitz.

It’s hard to fathom growing up during such world-shaking events. Airplanes and submarines were new technology, their might dominating the media. There were calls to arms on every street corner, footage of heroic soldiers bookending every movie, and a society unified in a singular drive towards a common goal. And in the service of that goal, Douglas’ older brother Keith had begun flying missions overseas with a Lancaster bomber squadron.

Flight Officer Keith Magrath

With a brother in the air force, Douglas would have been very much aware of the extraordinary dangers that would face him as a pilot. Over a fifth of British RAF pilots had been killed in the extreme destruction of the Battle of Britain in 1940. Yet, in October of 1942, nine-months after his eighteenth birthday, Douglas made the most important decision of his life. He followed in the footsteps of his older brother Keith, and enlisted with the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Although his specific reasons for enlisting are lost to time, the level of courage his decision shows is unmistakable. One is forced to wonder whether his parents, Ivan and Huldah, argued with him about his plans, whether the soft-spoken Douglas argued back, whether his many siblings were supportive, and whether Douglas himself agonized over the decision or it was inspired by hero worship of his older brother Keith.

Perhaps the secret lies in the timing. Douglas enlisted during the Battle of the St. Lawrence, after the first German U-boats had attacked Canadian merchant ships and warships along Canadian shores. Perhaps this was the moment that the war, which had loomed through years of Douglas’s life, became a real and present threat.

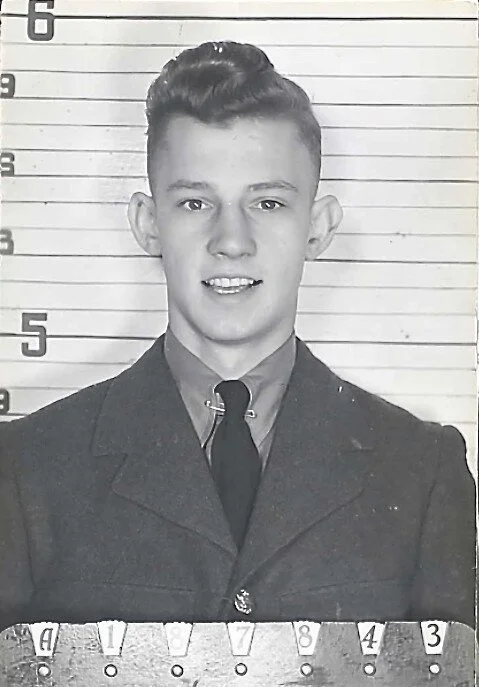

Douglas is pictured below at the beginning of his journey in the R.C.A.F. with the echo of a smile and a pair of big ears he’d yet to grow into. Along with the impressive uniform came a mountain of paperwork. He was compelled to recount his education and career (such as it was), his hobbies, interests, and medical history. He also had to name a beneficiary to receive his estate in the event of his death. As many did, Douglas chose his mother. He was then examined by a doctor who described him as “average or better material.”

At his first assessment, Douglas again distinguished himself. “Smart, keen, neat in his work,” wrote his Commanding Officer. “Good in sport and well liked. An earnest and pleasing lad. Reliable and intelligent. Recommend.” Unfortunately the task of flying did not come as naturally, and his Chief Flying instructor described him as “a little rough and inaccurate,” but claimed he “should improve considerably with experience.”

Nevertheless, as his training continued, Douglas’ results diminished, and by July, 1944 when, with a total of 107 hours spent in the air, he completed his Advanced Training and was certified ready for service, his final report had only one comment: “An average pilot who is prone to overconfidence.”

It is difficult to ignore the questions posed by the decline in those assessments. Was it simply a question of aptitude, or did the rigours of the training combined with the constant news from the front dispel - or increase - the young man’s heroic notions? Whatever the case, with a total of 107 hours spent in the air, Douglas Magrath achieved the rank of flying officer. According to the RCAF, he was ready to be deployed.

Ivan and Huldah Magrath now had three sons on active duty in the Air Force: Keith, the eldest, their third son Douglas, and Douglas’ younger brother Murray. The family at home was now engaged in another common experience for the time: the waiting game. Douglas’s father, Ivan, was described as a somewhat nervous man, but with all of his sons flying bombing raids in Europe that’s hardly surprising. His wife, Huldah, appears to have been the more stoic of the two. The newspapers were filled with the war, politics, and of course, notices of death. Who knows how many smiling young ghosts in uniform they read about while waiting for news of their three young men on the front lines?

On February 14th, 1945, only 7 months after being certified, and 6 months before the end of the war, Douglas Arthur Magrath participated in a bombing raid on the German city of Chemnitz, one of the largest rail junctions and railway repair shops in the Reich. The attack included 717 bombers, the Halifaxes, the Vancouvers, and Lancaster, from No. 6 Group. Douglas was among the first stream of 300 bombers. Three planes did not return.

Douglas and the six other members of his crew were declared missing. By late September of the same year, still missing, they were presumed dead. Ivan and Huldah received this news along with $396.66, the balance owing to Douglas for his service. There were also few personal effects, including six souvenir coins, a ring engraved with Douglas’ name, and a broken watch.

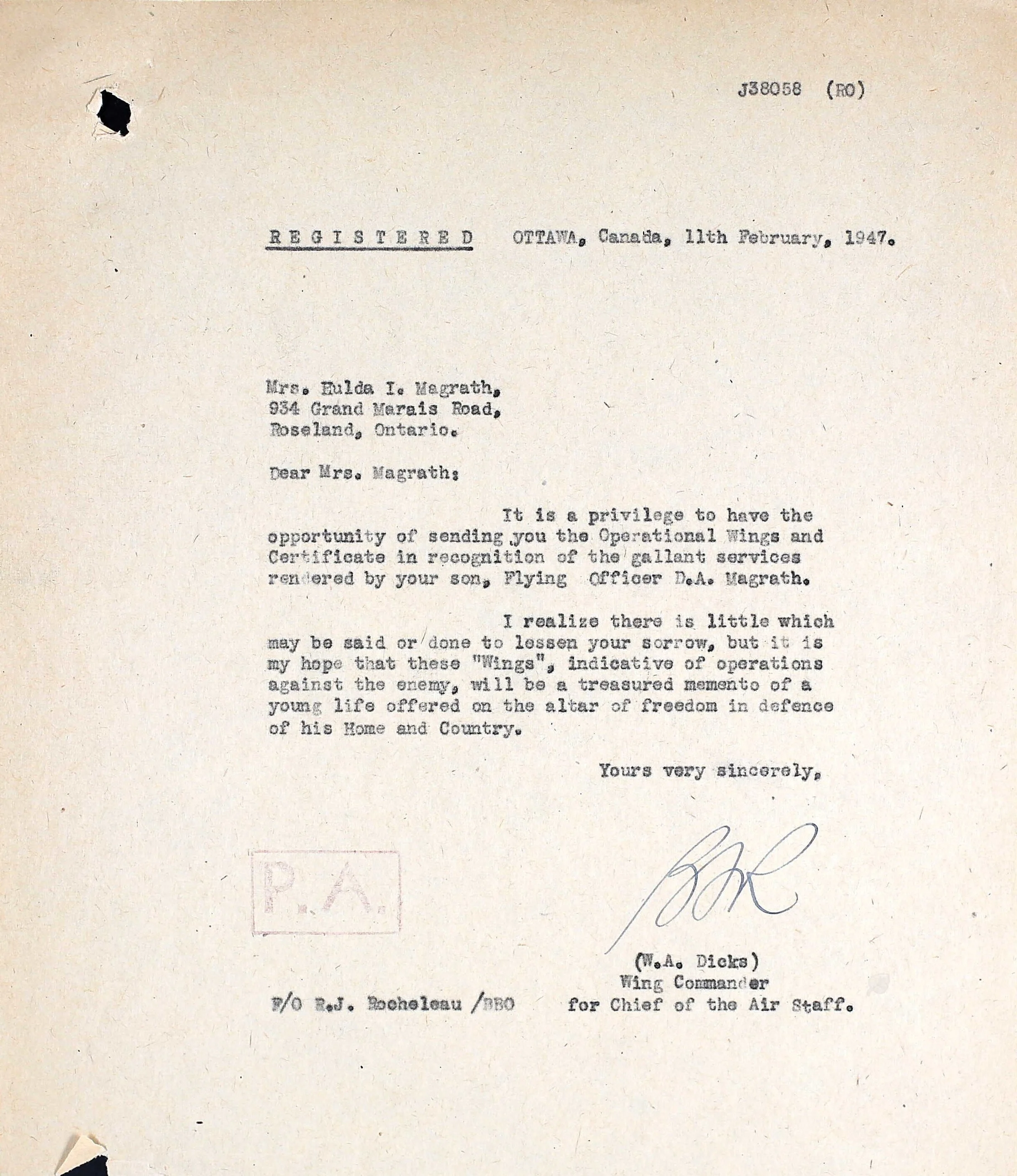

Two years later, in February of 1947, with Douglas still missing, Ivan and Huldah received Douglas’ Operational Wings, with a letter from Wing Commander W. A. Dicks who wrote the following:

“It is a privilege to have the opportunity of sending you the Operational Wings and Certificate in recognition of the gallant services rendered by your son, Flying Officer D. A. Magrath. I realize there is little which may be said or done to lessen your sorrow, but it is my hope that these “Wings”, indicative of operations against the enemy, will be a treasured memento of a young life offered on the altar of freedom in defence of his Home and Country.”

It was more than a year later, three years after the end of the war, that the Magraths finally gained closure.

“Ottawa, Canada, 16th July, 1948

Dear Mr. Magrath:

It is with regret that I again refer to the loss of your son, Flying Officer Douglas Arthur Magrath, but you will wish to know of a report received from our Missing Research and Enquiry Service.

The report states that Investigating Officers of this Service have ascertained your son’s aircraft crashed on a hillside near Tannenberg, which (as you know) is thirty-two kilometers from Chemnitz, Germany. A detachment of police had recovered the remains of the six members of the crew, who had lost their lives. They were buried in the local cemetery as six unknown Canadians. The grave was beautifully kept by a Frau Frieda Franke of Tannenberg. A rough cross of silver birch had been erected and Frau Franke had made a small memorial plaque with the following inscription in German “Here rest six Canadian airmen who met their deaths on the 14-2-45 in an aircraft crash.” The plaque was framed with brown varnished wood and had gold lettering on a black background. It was covered in front with glass.

Frau Franke wished to keep it for sentimental reasons and in view of the fact that she had kept the grave so well she was given permission to do so. The graves were exhumed resulting in the identification of all members. They have since been re-interred in the Berlin (Heerstrasse) British Military Cemetery in Berlin.

May I again offer you my most sincere sympathy in the loss of your gallant son.

Yours sincerely,

W.R. Gunn

Wing Commander

R.C.A.F. Casualties Officer

For Chief of the Air Staff.”

Whether Ivan, Huldah and the family were ever able to visit Douglas’ final resting place is unknown. Nor do we know whether they ever met or contacted the mysterious Frau Franke. Perhaps she too had a wiry son with big ears who didn’t come home.

The profound loss Ivan and Huldah Magrath experienced was an experience shared by countless other parents across the world, just a generation earlier. Frederick Newton Read was born in Owen Sound, Ontario, on January 23rd, 1891. At twenty-four years old, having graduated from the University of Toronto with a Bsc in Civil Engineering, Frederick already had a high level of education and an excellent career in Kerrobert, Saskatchewan when Canada joined the conflict in August of 1914.

His skills as an engineer also gave Frederick the means to contribute to the war effort from within Canada. As an established adult, he was faced with a complex decision: to remain in Saskatchewan where his home, family, and career were, or to enlist and put his life on the line for the greater good.

Frederick made his choice without hesitation. He answered the call of duty immediately and left his job to join the 2nd Field Company of Canadian Engineers. One of his first responsibilities was likely to help develop the Valcartier training site near Quebec City, which remains a base for Canadian Forces to this day. His time as a military engineer was brief, however, and within a year he had joined the Eastern Ontario regiment of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. By August of 1915, Frederick was on the front lines.

From autumn through winter, as a signaller on both the Somme and Armentieres fronts, Frederick lived in the trenches. Knee deep in a mix of mud and human waste, nostrils filled with the scent of gangrenous flesh, eating moldy rations, and living in constant fear of sniper bullets and deadly gas, he somehow managed to maintain his morale as the Allied and Central powers waited to resume their offensives. Unfortunately, his positive outlook provided little protection from the other hazards.

In the Spring of 1916 Frederick was “invalided” to Britain due to gas poisoning. Despite the horrible injuries gas can cause, such as third-degree burn-like skin blistering and ulcers in the lungs, Frederick was ironically very fortunate to have left the front when he did. His medical absence coincided with one of the biggest and most lethal offensives in human history, the Battle of the Somme.

Frederick struggled to recover for over a year, but even during his recuperation he served as a Regimental Sergeant Major at the P.P.C.L.I. Depot in Seaford. He was offered a commission with the Royal Engineers on three separate occasions that year. Each time he declined the promotion, preferring to remain with the unit with whom he had survived the trenches.

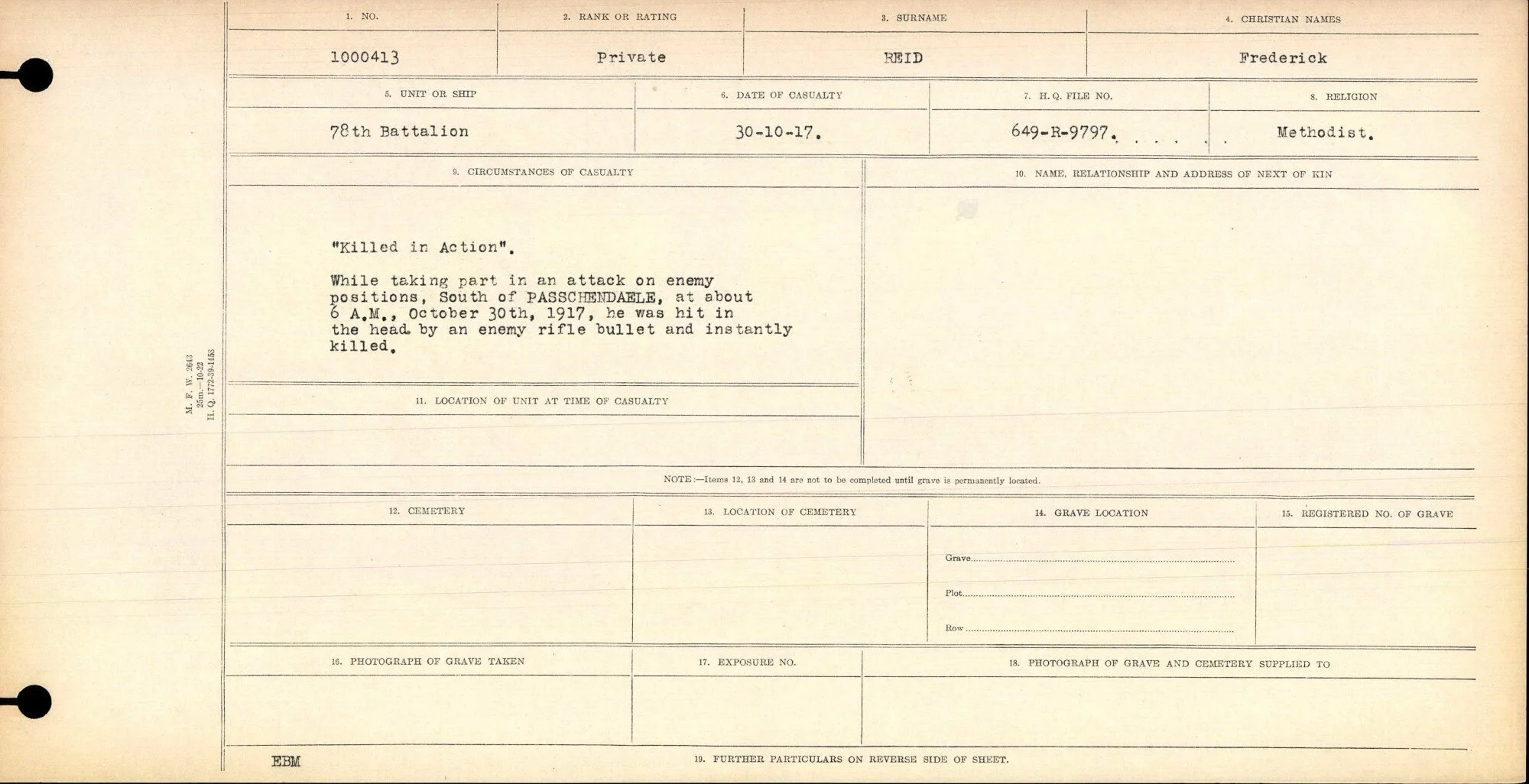

In August of 1917, as soon as he was well enough, and with full awareness of the hell-on-earth the frontline trenches represented, Frederick voluntarily returned to France with his unit. He even took a reduction in rank to Private in order to serve as an infantryman. Despite his best efforts, the young man was given a new commission in September, a promotion to the rank of Corporal, that would finally take him away from the comrades he had fought to stay alongside. But even then, Frederick chose to remain with the unit for one last upcoming operation: the Battle of Passchendaele.

Corporal Read’s division was held in reserve for the first stage of the offensive, which began on October 26th at 5:40 am. The unit received the slow trickle of information as battle lines crept forward and backward, outposts were attacked and captured, counter-attacked and abandoned, all the while artillery boomed, barrages raining down as often as four minutes apart.

By the 28th of October the first stage of the Passchendaele offensive was complete, and on the 30th of October, at 5:50 am, the main attack began. Corporal Read’s division, the Eastern Ontario Regiment, advanced along Ravebeek Creek, contending with the German forces over several strategic pillboxes. After multiple attacks, counter attacks, artillery strikes, and severe inclement weather, this part of Flanders was a wasteland of mud, foxholes, and barbed wire. Still refusing to leave his comrades behind at the last, Corporal Read was shot in the head by a sniper while attempting to rescue a fellow soldier. He was 26 years old.

According to official estimates, over half a million young men were killed over the course of that single, climactic battle. Like so many of them, Corporal Read’s body was never recovered. Instead, his name is memorialized at the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres, Belgium, beside the names of 55,000 other soldiers who lost their lives in the region. They rest there beneath a few simple words from Rudyard Kipling, who was the first Literary Advisor to the Commission:

“To the Armies of the British Empire who stood here from 1914 to 1918 and to those of their dead who have no known grave.”

We do not know many more details of Frederick’s life, but the few facts we do know shine a light on his gallantry. It seems fitting that every evening since 1928, buglers of the Last Post Association sound “The Last Post,” bugle call beneath the Menin Gate Memorial's arches. The call represents “a final farewell to the fallen at the end of their earthly labours and the onset of the night’s rest.” The ceremony has become part of the daily life of the city, and traffic is stopped on the roadway which passes beneath the memorial every day at this time. The only time the ceremony was interrupted was during the German occupation during the Second World War.

William Charles “Charlie” Powers was born on March 11th, 1920, in Brandon, Manitoba. He survived Scarlet Fever as a boy and grew to be an athletic teenager who swam, played hockey and tennis and, most extensively, baseball, which was his favorite. After high school, Charlie spent a few months at Brandon Vocational School studying radio transmission before enlisting in May of 1940. Like Douglas Magrath, Charlie chose the Royal Canadian Air Force.

A letter of reference to the R.C.A.F. from the principal of Brandon Collegiate Institute describes Charlie as “a young man of good character and attitude.” His initial Special Reserve Interview Report likewise describes him as a “gentlemanly young fellow,” healthy, slender, and a flashy dresser interested in amateur photography.

Despite a couple of early accidents during training (including one where the wing of his plane hit an unlit totem pole next to a hastily built runway), Charlie graduated from the RCAF program in May of 1941. For the next two years, he flew countless missions over France and Germany. Day in and day out, he lived the life so many young men did at that time, soaring again and again into the tumult of battle, hoping that he would be one of the lucky ones to return to base. With only sporadic leaves of absence, Charlie’s life for the next two years was subsumed to a routine that could have been curtailed forever any moment. Then, that seemingly ceaseless routine was in fact interrupted, but perhaps not in the manner he had anticipated. Charlie Powers found love.

Joan Molly Epps was a twenty year old widow with a baby. Her late husband, New Zealand born Graeme Holt Fenton, had also been a bomber pilot, killed in action in early 1942. We know very little about Charlie and Joan’s romance, but perhaps the couple would have preferred it that way. They were married on May 7th, 1943.

Like so many young men of the era, Charlie returned to duty only two days after his wedding. Hopefully, Flying Officer Powers’s marriage made his service easier. Despite the violence and chaos that filled his daily life, having a family to return to may have given the soldier a sense of purpose and of hope.

One benefit to being married was that Charlie began to receive more frequent leaves of absence to spend time with Joan and his adopted son. Within the year, Joan gave birth to a second son whom the couple named Gary William Powers. As he took to the skies again and again, Charlie now had three faces to picture waiting for him at home.

Unfortunately, Charlie would only get two chances to see his new son. The first was a 14 day leave within a week of Gary’s birth. The second was 7 days in March. In total, the four of them had 21 days together as a family. There were, of course, families who were less lucky.

In July, Charlie’s plane was shot down near Rennes, France. He was taken to a German hospital in Rennes with gunshot wounds to his left eye and both arms, and he died there two days later.

We have no record of how Joan was notified, but she and the children were the beneficiaries of Charlie’s estate, receiving the wages in September of 1945, after the war had ended. He was owed $994.64 for his service, the equivalent of roughly $15,000 today.

A year later, the two-time war widow and the two little boys moved to the hometown of her first husband in New Zealand where they lived for the rest of their lives.

William Charles “Charlie” Powers, the slender, flashy dresser who loved amateur photography and baseball, was buried in a civil cemetery in Rennes. Like Douglas Magrath, he was only later found, exhumed and re-interred. His body now rests in St. Charles-e-Percy War Cemetery in Calvados, France.

These brief glimpses into the lives of three soldiers leave many gaps and much to the imagination, but unfortunately imagination will have to suffice. We will never know Douglas Magrath’s intentions as he enlisted for war, or the name of the comrade Frederick Newton died trying to save, or the last words Charlie Powers said to his wife Joan and his two boys. These secrets are lost to us.

We do what we can to enshrine these gallant men, but no thanks can truly equal the gifts they fought to give us. They, and the hundreds of thousands of other young men their stories echo, sacrificed their future for our present.

Nevertheless, on this day of remembrance, Lest We Forget, we offer our deepest gratitude, and we do what we can to honour the immeasurable nobility which compelled them to lay down their lives for our sake. We pray that heroism of their like will be rarely needed but always found. Lastly, we hope they rest in eternal peace.