A Layered Approach Part II: Enhancing Historic Interiors with Mixed Reality

During the 2024/2025 school year, The Brown Homestead worked with an undergraduate Interactive Arts & Sciences class at Brock University to develop an Augmented Interiors project, creating a Mixed Reality application that digitally overlays the many layers of historic wallpapers uncovered in the John Brown House Ballroom back onto its physical walls. Learn about the process of designing and developing the interactive app, and explore how digital tools like Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality can enhance visitor experience and learning in museums and historic sites. This is the second part in a journal series exploring the wallpaper of our Ballroom.

The John Brown House was a gathering space for the Powers family, c. 1920s. Notice the decorative wallpaper frieze in the main floor hallway. STCM 2015.22.181.

After almost 200 years as a family farm home, the John Brown House (c.1802-1804) now currently serves multiple purposes as The Brown Homestead office, an adaptive reuse heritage conservation project, and as a historic site open to visitors. This dynamism requires a more creative approach to how we interpret the history and stories of the space. Because of this, the house cannot simply exist as a traditional historic house museum - decorated with antique furniture and stationed with costumed interpreters. Rather, the John Brown House is an active, constantly evolving historic site and this is reflected in our interpretation: the stories we share, and how we share them.

Any given day at the house is a flutter of activity - including the day that students in Brock University’s Interactive Arts & Sciences program first tested the Mixed Reality (MR) wallpaper visualization app they had spent the semester developing. It was mid-February and we also had volunteers at the house planning out the year’s community-based vegetable garden (oh yeah, add that to our multi-purpose site too!). While downstairs in the Dining Room, deep in discussion of which variety of heirloom eggplant seeds to plant, our staff and volunteers heard students’ exclamations of excitement coming from the upstairs Ballroom, and we leapt at the opportunity to join the fun.

Brock students and The Brown Homestead volunteers test our the Augmented Interiors app for the first time, February 2025.

Staff, students, and volunteers gathered together in the original entertaining space for the Brown family. We crowded around a tablet device to view a 3D model of the very room we were standing in on its screen, and using a simple scrolling feature, we were able to flip between different layers of wallpaper that once covered its walls at different periods in time. Despite our group coming from all different backgrounds and ranging in age from early-20s to mid-70s, we each were transfixed in child-like curiosity…. eager to take the tablet in our hands and try it out for ourselves.

Augmented Interiors Wallpaper Project

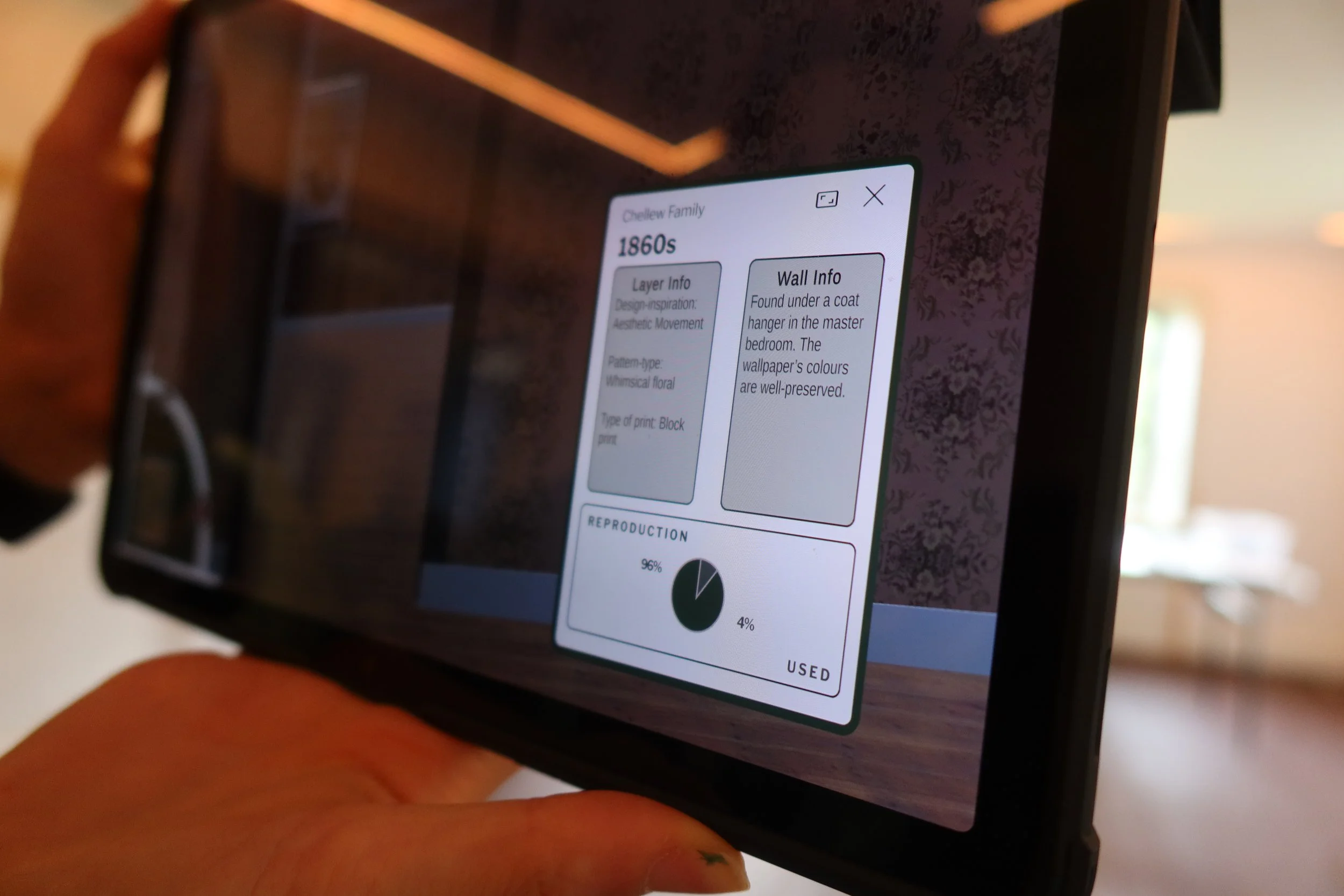

Using the tablet, we were trying out the first iteration of an MR application developed by Brock students. Termed “Augmented Interiors”, this project aims to digitally showcase and interpret various historic wallpaper uncovered within the Ballroom of the John Brown House while preserving the few original samples that remain intact. In the simplest terms, the students were tasked with creating a 3D model of the Ballroom’s walls and digitally reinterpreting the patterns of seven different wallpapers dated from the 1860s to the 1970s. Ultimately, the students developed both Augmented Reality (AR) and Mixed Reality (MR) prototypes of the same app. Upon review at the end of the semester, we decided we liked the MR version better, as it had a greater functionality and smoother user experience. With this MR prototype, users can scroll through the historic timeline of the room, distinguished by the families that occupied the house, and then apply the different wallpapers that would have once covered the walls. Interacting with the app’s features introduces users to the different families who called the John Brown House home and a brief account of each wallpaper layer, including the decade of production, pattern description, design school inspiration, as well as type of manufacturing process. The intended result is an interactive, mixed-reality experience that allows users to travel back and forth through time in one physical space.

A screenshot of the app designed for The Brown Homestead Ballroom, June 2025. Notice the bottom left corner of the screen, where users can scroll through different wallpaper patterns from different eras of the house.

Extended Reality in Real-World Museums & Historic Sites

The capabilities of Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR), and Mixed Reality (MR) are encompassed under the umbrella term of “Extended Reality.” Each tool enhances, extends and layers the physical space of a museum (or historic site) itself. VR refers to computer modelling that enables a person to interact with an artificial 3D environment in an immersive experience simulating reality. VR employs interactive devices like tablets and iPads, goggles, headsets, gloves, or full-on body suits to simulate an experience in the real world, from any location [1]. Alternatively, AR does not replace reality but rather enhances it - superimposing digital information on the user’s view of the real world [2]. As suggested in its name, MR is the mix or blurring of both, where a user simultaneously perceives and interacts with physical objects and stimuli in the real world as well as in a virtually constructed environment [3]. Augmented Reality and Mixed Reality often go hand-in-hand, but this is also when terminology and technology get quite complicated!

University of Cambridge Digital Humanities scholar Ronald Haynes frames these as digital tools that “augment knowledge” - combining physical spaces and tangible objects with digital images, videos, sounds and sensations to enhance learning, expand understanding, and deepen connection through a more immersive experience [4]. They extend the physical constraints of space, overlaying the past onto the present, and uncovering what was previously hidden or obscured [5].

Preserving the Original, Enhancing the Physical

The Brown Homestead’s Augmented Interiors wallpaper app uses digitized scans of surviving wallpaper fragments, and imagines how their full patterns might have covered the walls. With the physical samples preserved and kept safely in our collections, visitors can more meaningfully interact with the wallpapers of the Ballroom through the app - easily flipping between different patterns and eras as they move through the room. The app also visualizes the partition walls that once divided the room into bedrooms beginning in the 1860s. The capabilities of this Augmented Interiors project enables visitors to more fully imagine a picture of what we only have a few tangible remnants of. Their physical reality within the Ballroom is reimagined and enhanced.

(Left & Centre) Just one piece of wallpaper remains on the walls of the Ballroom, a strip with a whimsical floral pattern dated to the 1860s. (Right) Augmented Interiors enables visitors to envision the full pattern of the wallpaper as it may have looked to the people who decorated their bedroom at that time.

This is not to say that the singular strip of hand block-printed wallpaper dated to the 1860s that remains in the Ballroom is not valuable or meaningful. In fact, it is one of the most historically significant features of the room. Visitors who enter are immediately drawn to its eloquent Victorian pattern and deep hues of pinks, reds and greens. However, their engagement with the wallpaper as an artifact is limited. Currently, there is no text panel on display to offer historical context or significance. Given its age and material, visitors are asked not to touch the fragment (eventually, it will be preserved behind a plexiglass covering). And because it’s pasted onto the wall, the piece is quite literally flat and two-dimensional.

Providing New Access, Novel Connection & Alternative Preservation

Using Mixed Reality, Augmented Interiors enables visitors to engage with the wallpaper three-dimensionally and, even more, beyond the tangibility of the artifact itself [6]. Through the app, visitors can interact with full-scale digital reproductions of the surviving wallpaper where only remnants physically exist. They can walk around the Ballroom, holding up the tablet to visualize what the full patterns might have looked like on the walls. The app also enables visitors to interact with wallpaper layers they otherwise would not have access to, i.e. those removed from the walls. Furthermore, these wallpapers are now presented alongside other patterns that once decorated the same space. With users having the ability to flip between the different wallpapers on the app, these layers can be now in conversation with one another, rather than as they existed physically on the walls: tiered one on top of the other- with each new layer entirely covering the pattern below.

The app also offers further historical information to deepen the user’s connection to what they are digitally seeing through the screen, and what physically surrounds them.

In an era defined by technology and the attention economy, museums are in tough competition for visitors’ engagement. A museum visitor is often not interested in passively viewing an artifact - no matter the story or value attached. Most visitors are seeking emotional connection and authenticity - they want to feel, to be moved by the artifacts they are presented with and the stories told [7]. While Augmented Interiors does not quite yet offer an immersive experience that drops the visitor into the past like VR might, reimagining the space they stand within by blending the virtual with the real world does create a novel connection to the families that once lived here.

Lastly, Augmented Interiors not only helps preserve the wallpaper of the Ballroom as digitized artifacts but also the historic space itself through the 3D model of the room. We were reminded of this importance after the April 2025 loss of Glencairn Hall in Niagara-on-the-Lake. Built in 1832, this grand landmark on the Niagara River was destroyed by a fire, as were the stories embedded in its walls and floorboards.

Bridging the Academic with the Practical

The Augmented Interiors project was not our first with Brock University’s Department of Digital Humanities, and we plan for it not to be our last. In fact, The Brown Homestead was awarded the 2024 Experiential Education Community Partner of the Year – Humanities Faculty Category for our varied work with Brock University.

This AR version of the wallpaper app only made it to its first stage of design, as we ultimately felt the students’ mixed reality version of the app was more user-friendly. Here we see that the wallpaper layers are superimposed onto the back wall of the Ballroom. The black gap on the screen is the door leading into the upper hallway.

The students in the Interactive Arts & Science program are curious, innovative, and eager to blend the boundaries between the past and the future using digital tools. The project offered students real-world experience developing interpretive learning and engagement tools in a museum/historic site setting. They put theory into practice, applying what they’ve learned about technology design and user experience to the typical audience visiting our historic site. When designing the app, students had to consider visitor demographics, interests, digital literacy, and accessibility needs that may shape experience. For example, initially students were working to design a true Augmented Reality app that overlaid wallpaper layers onto the real walls of the Ballroom through the tablet’s camera. However, its interface was decided to be too complicated and thus may negatively impact user experience [8]. Instead, students opted to use the 3D model of the room to build a more cohesive experience for visitors using Mixed Reality.

While the students learned a lot from developing the two different app prototypes, The Brown Homestead staff also learned a lot from the students. We are heritage professionals who mainly work with what’s tangible - whether we’re using our hands to restore built heritage materials on site, or to physically guide visitors up staircases and into rooms on tours. Even in digital research projects, like Mapping The Brown Homestead, we’re interpreting historical maps that were made as physical objects before later being digitized. The Augmented Interiors project required students to take surviving wallpaper fragments and reproduce the pattern to cover a full wall. This required studying similar historic wallpaper patterns from the era, as well as a bit of math to measure and replicate each sample. The results were entirely reproduced wallpapers that exist only in the digital sphere - they cannot be experienced in the real-world - only on the app. Without this digital tool, visitors to the Homestead would not be able to imagine the full scale of these wallpapers, nor even have access to them.

“While we worked there was a lot of inquiry towards finding the origin and history behind each wallpaper. It was very interesting to learn that the type of design, colours, and material of the wallpaper, and how it was made, can tell a lot about its history. In the making of the AR app, I learned the multiple ways one could transfer a recovered and illustrated wallpaper onto the walls of The Brown Homestead. The team I worked with used a variety of skills including 2D art, 3D art, UI Design, coding, and imagination. ”

At the conclusion of the 2024/2025 school year, the students handed off the Augmented Interiors app to The Brown Homestead staff, but the app is not quite final. A major component of developing digital tools for public use is actually testing their use with the public. Intended-use rarely translates to actual-use. Does Augmented Interiors offer visitors the connection to, and feeling of, the past that we intended? Does the MR prototype enact the kind of curiosity and discovery that we hoped? With these questions now ready for answers, Augmented Interiors continues to be in an experimental phase as we work to enhance our visitors’ learning experience.

Help us Test it Out!

This is where you come in. Visitors are invited to use the students’ app in the Ballroom of the John Brown House and test out how it works. We are eager for feedback on how to improve it for a more immersive and engaged user experience.

You can visit us all summer long. We’re open to the public Thursdays - Saturdays through to Labour Day weekend. Feel free to drop by or book a guided tour. We’re open 10 a.m. - 4 p.m.

We’re more than just historic wallpaper here, but heritage craftsmanship and conserving heritage materials are definitely passions of ours. Come see for yourself how we are interpreting the site of the oldest home in St. Catharines, and immerse yourself in the stories - and wallpaper decor - of the farming families that made this place a home.

Sara Nixon is a public historian and the Director of Community Engagement at The Brown Homestead.

Footnotes

[1] Weiran Zhang & Zhaoyu Chen, “How does virtual reality facilitate museum interpretation? The experience of perceived authenticity,” Tourism Recreation and Research (2024): 1.

[2] Theodore Koterwas et. al, “Augmenting Reality in Museums with Interactive Virtual Models” in Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality: Empowering Human, Place and Business, eds. Timothy Jung and M. Claudia tom Dieck (Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018): 365.

[3] Richard Skarbez et. al. “Revisiting Milgram and Kishino’s Reality-Virtuality Continuum,” Frontiers in Virtual Reality, Vol. 2 (March 2021): 2.

[4] Ronald Haynes, “Eye of the Veholder: AR Extending and Blending of Museum Objects and Virtual Collections” in Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality, 81.

[5] Zhang & Chen, “The experience of perceived authenticity,” 2 & 7.

[6] Larissa Neuburger and Roman Egger. “Augmented Reality: Providing a Different Dimension for Museum Visitors” in Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality, 73; Haynes, “Eye of the Veholder,” 80.

[7] Jin et al. (2020) identifies three types of authenticity: original authenticity, which is experienced through artifacts and exhibits; interactive authenticity, experienced through text, hands-on activities, and participatory features; and emotional authenticity, created through an immersive experience that enables dialogue and connection to new voices, perspectives, and cultures. Zang & Chen, “The experience of perceived authenticity,” 9.

[8] Scholars warn of the thin line between the capabilities of AR and VR to enhance or detract from a visitor’s museum experience. Difficulty using the technology or a poor design run the risk of taking users out of an immersive experience, distracting from their engagement and enjoyment at a museum. See: Koterwas et. al, “Augmenting Reality in Museums,” 366; and Zhang & Chen, “The experience of perceived authenticity,” 6 & 13.