Records as Storytellers

The Power of Documentation in Conserving our Heritage Buildings

"You die twice. One time when you stop breathing and a second time, a bit later on, when somebody says your name for the last time". [1] It’s a sober message. But what if, instead of a person, this was about a place? The following article illustrates how documenting history is a valuable tool for the conservation of Canadian buildings, and how our communities are making it happen.

Lafontaine, Charlie, Annie and Mabel Powers (L to R) pose around the front porch of the John Brown House, c. 1910. Photo courtesy of Ethel (Powers) Simpson.

Have you ever wondered about the history of your house? Who lived there over time, what their hobbies were, what activities took place throughout the various rooms, on the front lawn, or in the backyard? Was the home a witness to the birth of new life? Did it observe more sombre moments of death or tragedy? Which of life’s beautiful and precious moments took place in those hallways, and who were the beings that lived those experiences? As remnants of these people appear throughout the building, they become increasingly rounded out as real characters. We are left to wonder… Why did they choose that specific wallpaper pattern? Why did they cut out the tongue and groove in the old kitchen floorboards? What were they thinking?

These are the sorts of questions we ask in our work as historians and heritage professionals about the everyday places and spaces around us. Fortunately, there are countless repositories, libraries, and archives out there (both digital and physical) that provide us with answers to many of these queries.

At The Brown Homestead, we are advocates of heritage conservation for a variety of reasons. We have seen historic sites become places of community connection. We know that adaptive reuse is a more environmentally sustainable alternative to demolition. We could cite the benefits of historic preservation all day, but in this article we will be focusing on just one element: documentation. Not just as a means to an end, but as an integral part of the overall objective.

There are three main elements that we will be addressing here:

Historical Reports as Legal Safeguards

Records as Crucial Storytelling Tools

Files as Fodder for a Digital Future

Historical Reports as Legal Safeguards

Upon hearing the word conservation, you might immediately think of the physical acts of cleaning, stabilizing, and monitoring the condition of a valuable item or building. Fortunately, in Canada our governments have put forward legislation designed to help protect these significant places and spaces (including cemeteries, cultural landscapes, archaeological sites, etc.) and support the work of conservators. Properties designated under the Ontario Heritage Act are given legal protection against demolition or excessive or irreversible changes that would remove or alter their heritage character, and promote knowledge of the place’s story in the community. Furthermore, depending on the municipality, designation may open opportunities for financial incentives to aid in conservation work.

One of the first steps in the designation process, presenting the case upon which these legal decisions rest, comes in the form of the Heritage Designation Report.

Designation has become a dirty word in some circles. There is fear around losing agency when it comes to renovation choices, increased insurance and maintenance costs, and resale value. A lot of these fears are myths that can be busted through conversations with your municipal planners. In fact, quite a few municipalities assist heritage homeowners by offering tax relief programs and grants towards any necessary conservation and/or restoration work. These are wonderful examples of government and citizens working together towards a common goal.

A recent study (2023) from McMaster University even concluded that heritage designations positively impact the sale price of residential properties in Hamilton.

Two years ago we noted that when it comes to these harmful myths, the solution lies in education, community engagement, and more broadly accessible information about the heritage protections that exist and how to leverage them. You can read more about this in our article “Reflecting on Heritage in Ontario”, or if you’re an auditory learner, listen to Chloe Richer on The Open Door Podcast Season 3 Episode 6, “(Mis)Understanding Heritage Designations”.

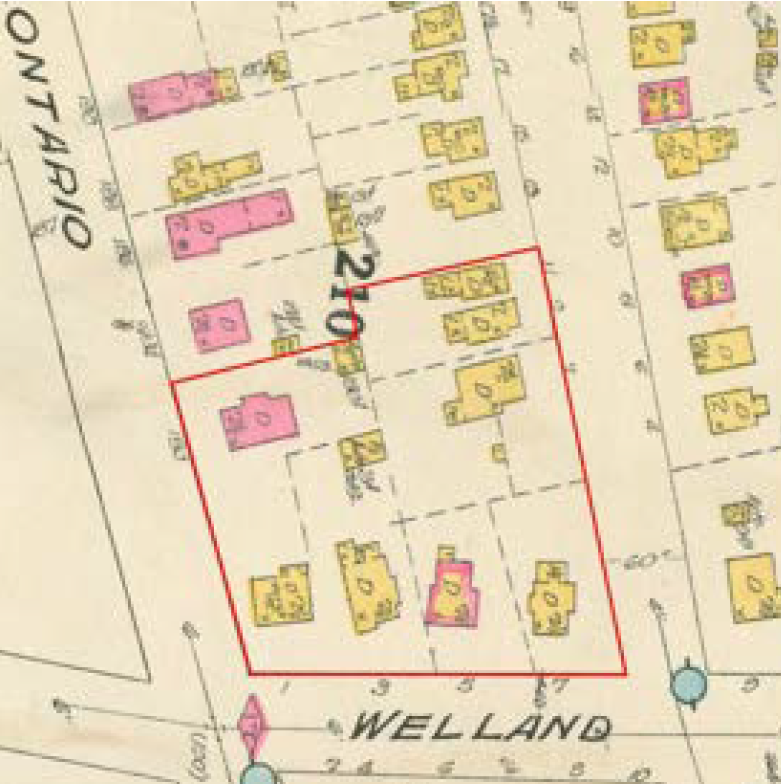

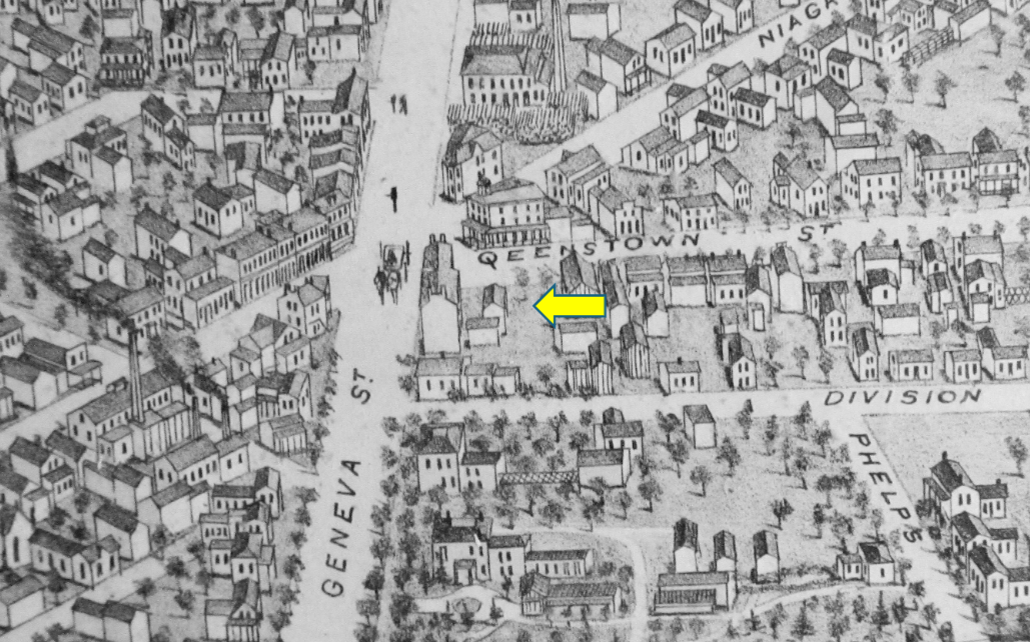

The St. Catharines Heritage Advisory Committee has designated approximately 42 individual properties since the OHA’s inception in 1975. Large areas of the city have also been given blanket designations, and there have been perhaps a dozen research reports written during the past fifteen years or so. The purpose of these reports are to present a detailed record of the property with the intention to designate it as historically, culturally, and/or architecturally significant. However, this process takes months to complete. St. Catharines’ planning staff, despite best efforts, have managed to designate just 10 properties in the last decade. [2] They have also added 52 properties to the municipal register in that time, but this register is slated to be removed by January 1, 2027, as per the province’s Bill 23 mandate (2024). [3]

As one of the first steps, the process of compiling a heritage designation report requires a great deal of time and effort. This is difficult to come by on the municipal level, and much of the work is left to dedicated community volunteers to complete. Planning departments and volunteer heritage committee members must learn about where and how to access historical information about these spaces in order to present the argument for why it demonstrates cultural, architectural, and/or contextual heritage value. At the local level, the level of engagement varies. Some municipalities have enthusiastic planners and vibrant volunteer advisory committees, and others are plagued by conflicting views towards heritage and development - and that’s if they even have a heritage planner or volunteer committee operating at all.

In the same vein, cultural resource management (CRM) professionals use historical records to better understand the sites they interact with. This archival work is accomplished alongside physical surveys, excavations, and interactions with developers and stakeholders. The historical reports they produce - Stage 1 Archaeological Assessments - can determine archaeological potential and recommendations for further pedestrian or test pit surveying.

While these reports as tools for conservation and damage mitigation require quite a bit of behind-the-scenes research time and effort, their value cannot be understated. Not only do these reports provide access to critical information, but they also provide a case for support. They inform decision-making. In this way, historical research is not just a means to an end. Rather, it becomes an integral part of the overall objective.

Examples

At The Brown Homestead, we teach property researchers how to use Onland: the provincial portal housing Ontario’s digitized property records formerly kept in land registry offices. Our Land Registry Workshops provide an introduction to the written records and how to interpret them. If you want to know how to access information about a place, this is a great first step!

Curious about a historic building in St. Catharines? Full designation reports are held in the Planning Department at City Hall and copies exist in the Special Collections room in the downtown library.

Ultimately, historical research, analysis, and final report compilation exist as a fundamental step in the designation process. By creating this formal document, people are compiling a story of that place, which brings us into our next point highlighting the value of libraries and archives as institutions caring for and providing access to the records needed to do this critical work.

Records as Crucial Storytelling Tools

Documentation of a space means telling its story (as best we can) up to the present day, providing comprehensive information for future property owners, conservators, and community members. Compiling a historical record ensures our future generations will have the ability to observe and understand why these places once mattered to people in our communities.

Our first point shows how report compilation acts as a tool for conservation when it comes to building a case for designating heritage properties in Ontario. But we can take it even further here, arguing that by compiling a historical account of a place, we are also preserving its memory. This can be valuable in a multitude of ways, beyond designation. Going back to the quote in the beginning… if you preserve the story of a place, aka its memory, you preserve its intangible significance.

It may be helpful to think of the reverse — if you are simply viewing a structure without any knowledge of its history, it’s simply a beautiful outline — visually appealing, but hollow inside. The cultural and historical significance of the people involved is missing, if you have no knowledge of how it came to be crafted, who occupied the space, and what happened there over time. The point here is that the intentional documentation of a place’s historical record informs how we understand the space. It is not simply enough to say “This place matters!” without being able to answer the crucial question of “Why?”

This point ties into a larger problem that we’re currently facing with the proposed elimination of the Canadian Register of Historic Places (CRHP). Documentation of Canada’s nationally recognized historic places is under threat. The CRHP narrows the vast geography of our country that otherwise isolates us from each other, and therefore this register is a tool for national recognition and nation-wide placemaking. If these places are erased from our national conscience, the buildings themselves consequently are at a greater risk of being lost. The National Trust has put out a Request for Proposals for a project to investigate redevelopment options for the CRHP, with a February 19 deadline. The purpose of the project is to assess technical, functional and governance options for a renewed national, searchable and publicly accessible catalogue of historic places. Consider entering a proposal and be part of charting a new path for the CHRP!

Historical records include, but are not limited to, land registry records, historical maps, aerial photographs, census records, voters lists, birth, marriage, and death records, wills and surrogate court records, historic images, postcards, diaries, letters, newspaper articles, architectural drawings, business records, and more. Report writing involves the process of consolidating information from these resources, analyzing the material, and presenting the information in a condensed, straightforward way. A good report will weave together a narrative! As time allows, there are additional avenues for even further investigation. Information gathered from oral histories and videos, physical evidence presented by relevant artifacts, and features determined by archeological surveys, and/or interpreted via a structural building analysis can also round out our understanding of these places and spaces.

A well rounded understanding of a space thus requires the collaboration of cultural organizations and knowledge keepers, architects, engineers and carpenters, anthropologists, geographers, and environmental experts, alongside librarians, archivists, museum professionals and historical researchers.

In the end, we are left with a story, as best we can tell it.

Files as Fodder for a Digital Future

Project Manager Mackenzie Campbell documents wallpaper in the JBH Ballroom, 2022.

Finally, we want to touch on an element that cannot go unmentioned in this article about documentation. As technology advances, there are more and more opportunities for using digital tools to recreate spaces and/or features that no longer exist, to help people imagine what they may have looked like in the past. This sort of work can only be done, however, if a careful documentation of the space was completed prior to decay or demolition.

Here at The Brown Homestead, we have been collaborating with Brock University on a mixed reality application for visitors to experience the many layers of our ballroom’s historic interior. Users can flip through the virtual layers, from the early days of the Brown family’s multi-purpose use of the space, through the addition of an 1860s wall by the Chellews, past the 27 layers of wallpaper and friezes added over the next century, and into our present rehabilitation of the room back into a community gathering and event space.

This application was made possible through the careful documentation and conservation of the physical wallpaper pieces, as well as photographs of the room from every angle and at every stage of rehabilitation. Last year, students from Brock’s Digital Humanities Department used data acquired from Dr. John Bonnett to build a prototype that we show our visitors during house tours. In 2022, Dr. Bonnet used a 3D FARO scanner to create a point cloud that was then converted into a 3D model. This impressive LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology uses a rotating laser beam to create a three-dimensional, measurable and coloured digital replica of the room. Read more about it in our June 2025 article:

Because not everyone has access to such equipment, another method of documentation for this same purpose of recreating 3D models comes in the form of photogrammetry. This technique uses overlapping photos that provide spatial data for the creation of a digital “twin” of the real space. Museums and institutions have been working with this technology to track changes over time and recreate features, rooms, and/or buildings that have been damaged or destroyed. These have proven to be exceptional tools for increasing public engagement with historic sites and artifacts.

Dr. John Bonnett scans the summer kitchen at the John Brown House, 2022.

The work being done to document our history is a critical part of the efforts being put towards heritage conservation here in Canada. They inform decision-making when it comes to these sites of shared significance, and they preserve the memory of those involved. The historical record brings to life the unique stories of those who crafted our communities’ built heritage, and their preservation allows us to create new memories in the present.

Which spaces have meaning to you? What places do you consider “home”? Submit your photo to be a part of a digital archive exploring what Niagara means to the people who call our region home.

“Niagara In Focus”

Community Photo Project

Submit your photo to be a part of a travelling exhibit and digital archive exploring what Niagara means to the people who call our region home.

Jessica Linzel is a historical researcher and the Director of Research & Collections at The Brown Homestead.

Footnotes

[1] We can’t attribute a single author to this quote. https://quoteinvestigator.com/2025/10/15/die-twice/

[2] Information courtesy of Brian Narhi, St. Catharines Heritage Advisory Committee Chair.

[3] “The Register was initially created as a heritage inventory tool for municipalities to keep track of the properties of heritage value in the communities, as well as to offer baseline protections outside of full designation by way of limited, short-term (60 day) demolition controls. This tool was particularly useful for small and rural municipalities with too few resources to undergo the designation process for the heritage properties in their communities. However, Bill 23 fundamentally changed the very identity of the Municipal Heritage Register. Now, there is a time limit on those properties included in these municipal inventories. After January 1, 2027, if the property is not designated, it is removed from the Register and not to be added to the inventory again for five years, negating the purpose of the inventory in the first place.” Sara Nixon, “Reflecting on Heritage in Ontario”, The Homestead Journal, March 24, 2024.